A brief History of Cyprus

British Period (1878 - 1960)

Britain had no involvement with Cyprus before 1878, but the island's sudden and peaceful absorption into the British Empire is not difficult to explain. The keystone of the British imperial policy in the 19th century was to protect the sea route to India, and to support the Ottoman Empire against the ambitions of an ever-expanding Russia. The Crimean War of 1853-6 had been fought for just such a purpose.

In 1875 Britain purchased a key block of Suez Canal shares. Three years later another crisis caused by Russian ambitions over the disintegrating Ottoman Empire was defused, and the British prime minister began to show signs of distinctly predatory interest in the area nearest to the Suez Canal. During these negotiations in 1878 Cyprus was acquired by Britain in order to assist the Ottoman Empire. The nature of that assistance was to be more fully revealed four years later, in 1882, when Britain absorbed into her own Empire the old Ottoman province of Egypt.

While the Greek Cypriots had at first welcomed British rule hoping that they would gradually achieve prosperity, democracy and national liberation, they were soon disillusioned. The British imposed heavy taxes to cover the compensation which they were paying to the Sultan for having ceded Cyprus to them. Moreover, the people were not given the right to participate in the administration of the island since all powers were reserved to the High Commissioner and to London. A few years later the system was reformed and some members of the legislative Council were elected by the Cypriots, but in reality their participation was very marginal.

The British faced two major political problems on the island. The first was to contain the desire for union with Greece (enosis). The second was the consequential problem of keeping the two communities in harmony once the Turkish Cypriots began to respond to enosis by calling for partition (taksim) as a defence against their being Hellenised, as they saw it. The Greek-Cypriots could easily claim that they had a strong case in history and they constituted between three quarters and three fifths of the population.

Under the convention of occupation, Cyprus was still a part of the Ottoman Empire, and the excess of revenue over expenditure, agreed at £92,000, was paid annually to the Sultan.

The British undertook an extensive program of public works, including the construction of roads and bridges, drinking and irrigation water supplies, and even a railway line linking Nicosia to Famagusta and Guzelyurt (Morphou). In addition, port facilities were improved, and administration buildings, schools and hospitals were built.

When Turkey sided with Germany in World War I, Britain annexed the island, annulling the convention of 1878. In 1915, Great Britain offered Cyprus to Greece in return for joining the allied cause, but this suggestion was rejected, and with it the chance of enosis, the striving to which would cause so much strife in the future. Ten years later, Cyprus became a Crown Colony, and the High Commissioner was replaced by a Governor.

Meanwhile, the enosis movement, aiming for union with Greece, was growing within the Greek Cypriot community, fostered by the powerful Orthodox Church. The movement erupted into island wide riots in 1931, during which Government House was burnt to the ground. The uprising was crushed, and the Legislative Council abolished, thus eliminating the local voice in government decisions.

|

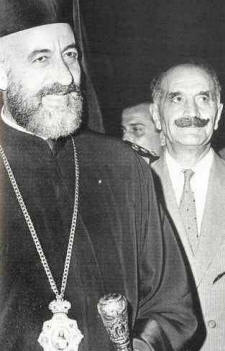

| EOKA Leaders Makarios and Grivas |

In 1941, during the second world war, Britain again offered Cyprus to Greece, this time in return for military action in Bulgaria. Again the suggestion was rejected.

After World War II, when 30,000 Cypriots fought in the British army, calls for enosis were renewed. A plebiscite organized in 1950 by Makarios, later Archbishop Makarios III, showed that 96% of the Greek Cypriots supported union with Greece. However, it has been reported that excommunication was a stick used to encourage the overwhelming vote. Furthermore, it is doubtful that many Cypriots understood the full implications of enosis, quite apart from the fact that it was anathema to the Turkish Cypriot minority.

Post war attitudes were against the old ideas of colonialism, and when Greek Cypriot demands for self determination resulted only in the offer of a new constitution, the signal was given for Colonel George Grivas to launch EOKA. (National Organization of Cypriot Fighters) This armed struggle against British rule began in April 1955, and was abetted in the churches by the clergy, with the blessing, indeed the leadership, of Archbishop Makarios III. The latter was exiled to the Seychelles 14 months later after the call for enosis had been outlawed. The Turkish Cypriot community spawned their own movements; taksim called for the division of the island; TMT was the Turkish Cypriot resistance movement.

After a conference attended by Greece, Turkey and Britain in June 1955 failed to achieve a solution, Greece applied to the United Nations in 1957 and again in 1958, claiming the right of self determination for Cypriots. This claim, of course, did not take into account the position of the Turkish Cypriot minority, and as a counterthrust, Turkey suggested a partition of the island.

With the death toll rising above 500, the British were anxious to find a suitable formula for independence. This was eventually hammered out in the Treaty of Zurich, and on 19th February 1959, Makarios III, Dr. Fazil Kucuk (the Turkish Cypriot representative), plus the prime ministers of Britain, Greece, and Turkey, all signed the London Accord, granting Cyprus independence. The agreement, which left Britain with the sovereign base areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, provided guarantor powers of intervention to Britain, Greece, and Turkey.

The Republic of Cyprus came into being on 19th August 1960, and on 20th September it joined the United Nations, and the British Commonwealth.